AICA Stroke Analysis: A Critical Look at Rare Brain Damage and Daily Life

By Ellia Ciammaichella, DO, JD

Triple Board-Certified in Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Spinal Cord Injury Medicine, and Brain Injury Medicine

Quick Insights

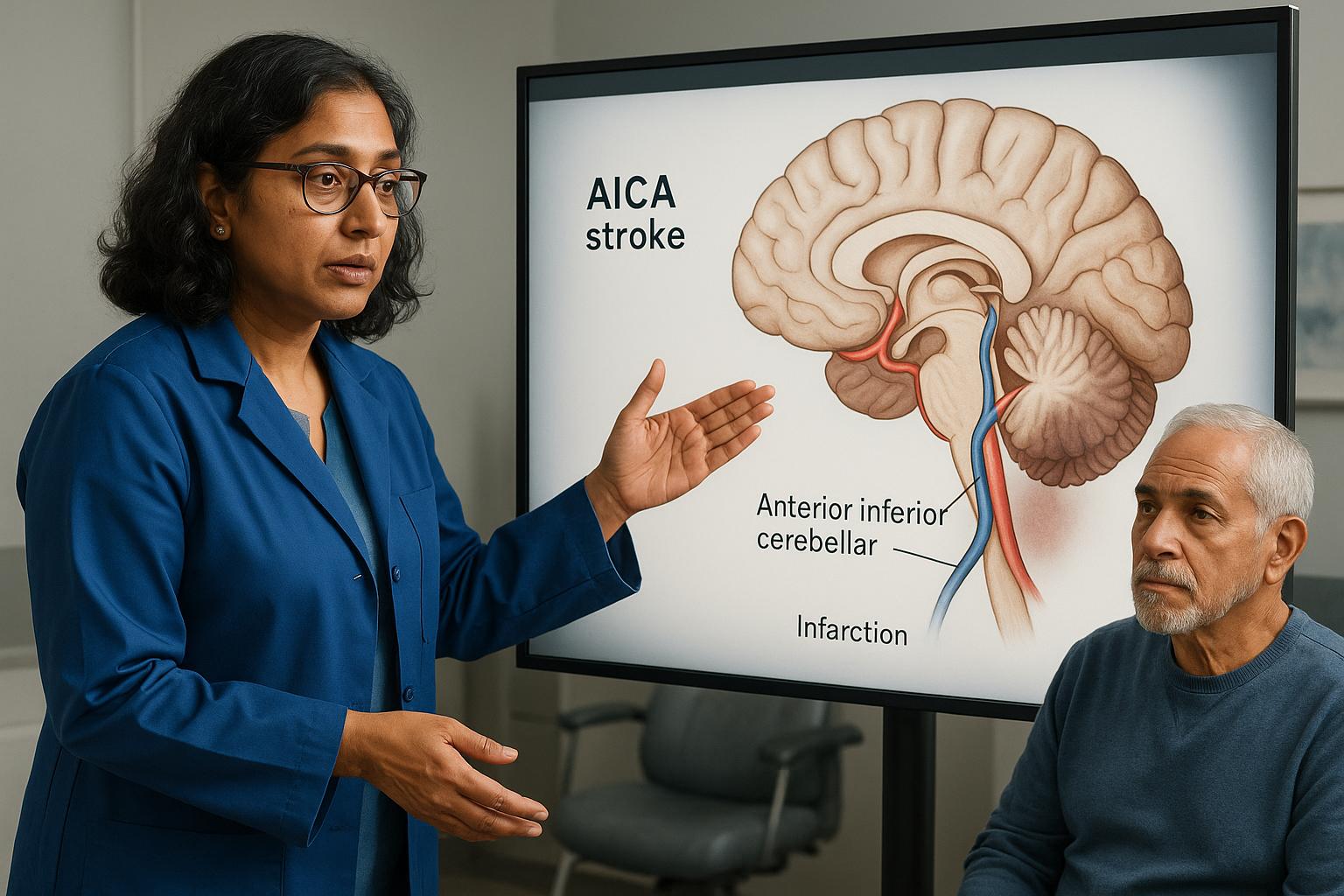

An AICA stroke occurs when blood flow stops in the anterior inferior cerebellar artery. This vessel supplies the lower cerebellum and brainstem structures. When blocked, patients often experience sudden vertigo, hearing loss, and facial weakness. The middle cerebellar peduncle and lateral pons are commonly affected. Early imaging with MRI helps confirm the diagnosis and guide treatment decisions.

Key Takeaways

- AICA territory infarcts frequently cause vertigo, ataxia, facial palsy, and hearing loss together.

- Diffusion-weighted MRI reveals lesion patterns involving the middle cerebellar peduncle and inferior lateral pontine area.

- Cerebellar strokes carry significant morbidity, with outcomes depending on infarct size and location.

- Anatomic variability in AICA territory creates diagnostic challenges and influences symptom presentation patterns.

Why It Matters

Understanding AICA stroke helps explain why dizziness and balance problems appear suddenly with other neurological symptoms. Recognizing these patterns supports timely medical evaluation and realistic recovery planning. For legal professionals, knowing how cerebellar ischemia affects daily function clarifies impairment claims and long-term disability assessments.

Introduction

I have extensive experience evaluating neurological injuries where sudden symptoms create diagnostic uncertainty. As a triple board-certified physiatrist with medical and legal expertise, I have worked with diverse cases involving cerebellar ischemia and stroke.

An AICA stroke occurs when blood flow stops in the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, a vessel supplying the lower cerebellum and portions of the brainstem. When this artery becomes blocked, patients often experience sudden vertigo, hearing loss, and facial weakness together. Medical evidence shows that AICA territory variability creates diagnostic challenges, since symptom patterns depend on which structures lose blood supply.

Understanding how cerebellar ischemia causes dizziness and balance deficits helps explain why these symptoms appear suddenly alongside other neurological signs. For legal professionals, recognizing these patterns clarifies how stroke location affects daily function and long-term impairment.

This article explains AICA stroke mechanisms, imaging findings, and recovery trajectories using evidence-based analysis.

What Is an AICA Stroke?

An AICA stroke occurs when blood flow stops in the anterior inferior cerebellar artery. This vessel supplies the lower cerebellum and portions of the brainstem, including the middle cerebellar peduncle and lateral pons. When the artery becomes blocked, the structures it feeds lose oxygen and begin to die within minutes.

The AICA originates from the basilar artery and follows a variable course through the posterior fossa. Anatomic variability means the exact territory affected differs between individuals. Some patients have a dominant AICA that supplies a larger region, while others have smaller branches with overlapping supply from adjacent vessels.

In clinical practice, physicians often encounter diagnostic uncertainty due to anatomic variability when evaluating stroke cases. Symptom patterns in stroke may vary depending on individual vascular anatomy.

Understanding AICA territory helps explain why certain symptom clusters appear together and why imaging findings may not always match clinical presentation. For a more detailed look at stroke territory symptoms and advanced imaging, you can read about expert recognition of territory-specific stroke presentation.

Common Symptoms of AICA Territory Infarcts

Patients with AICA strokes typically present with sudden vertigo, hearing loss, facial weakness, and ataxia. Clinical studies document vertigo and ataxia as prominent features, often appearing together with cranial nerve deficits. The combination reflects damage to both cerebellar structures and brainstem nuclei.

Vertigo occurs because the AICA supplies the vestibular nuclei and inner ear structures. Patients describe severe spinning sensations that worsen with head movement. Nausea and vomiting often accompany the vertigo, making early diagnosis challenging since these symptoms mimic peripheral vestibular disorders.

Hearing loss may be sudden and complete in the affected ear. The AICA supplies the labyrinthine artery, which feeds the cochlea. When this branch becomes blocked, auditory function stops immediately. Facial weakness appears on the same side as the hearing loss, reflecting damage to the facial nerve nucleus in the pons.

Research shows that diffusion-weighted imaging confirms the clinical spectrum of vertigo, facial weakness, and ataxia in AICA territory infarcts. Ataxia affects the limbs on the same side as the lesion, causing unsteady gait and impaired coordination. Patients may fall toward the affected side when attempting to walk.

How Imaging Reveals AICA Stroke Patterns

MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging reveals AICA stroke patterns within hours of symptom onset. Imaging studies show lesions involving the middle cerebellar peduncle and inferior lateral pontine area in characteristic patterns. These findings help confirm the diagnosis when clinical symptoms suggest posterior circulation ischemia.

Diffusion-weighted sequences detect restricted water movement in areas of acute ischemia. The middle cerebellar peduncle appears bright on these images when AICA territory is affected. Lesions may extend into the lateral pons, flocculus, and anterior inferior cerebellar hemisphere depending on the exact occlusion site.

Advanced imaging defines territory involvement and feeding arteries with greater precision than older techniques. CT scans often appear normal in the first 24 hours, making MRI essential for early diagnosis. Vascular imaging with MR angiography may show the occluded AICA segment directly.

In medico-legal cases, I correlate imaging findings with functional outcomes. Damage to critical structures like the middle cerebellar peduncle typically produces more severe balance deficits than peripheral cerebellar lesions, which matters when assessing permanent impairment. This relationship between anatomy and function matters for disability assessment. For a deeper look at the assessment of impairment and the nuances of diagnosis, see the expert recognition guide on AICA stroke symptoms.

Understanding Cerebellar Ischemia and Balance Deficits

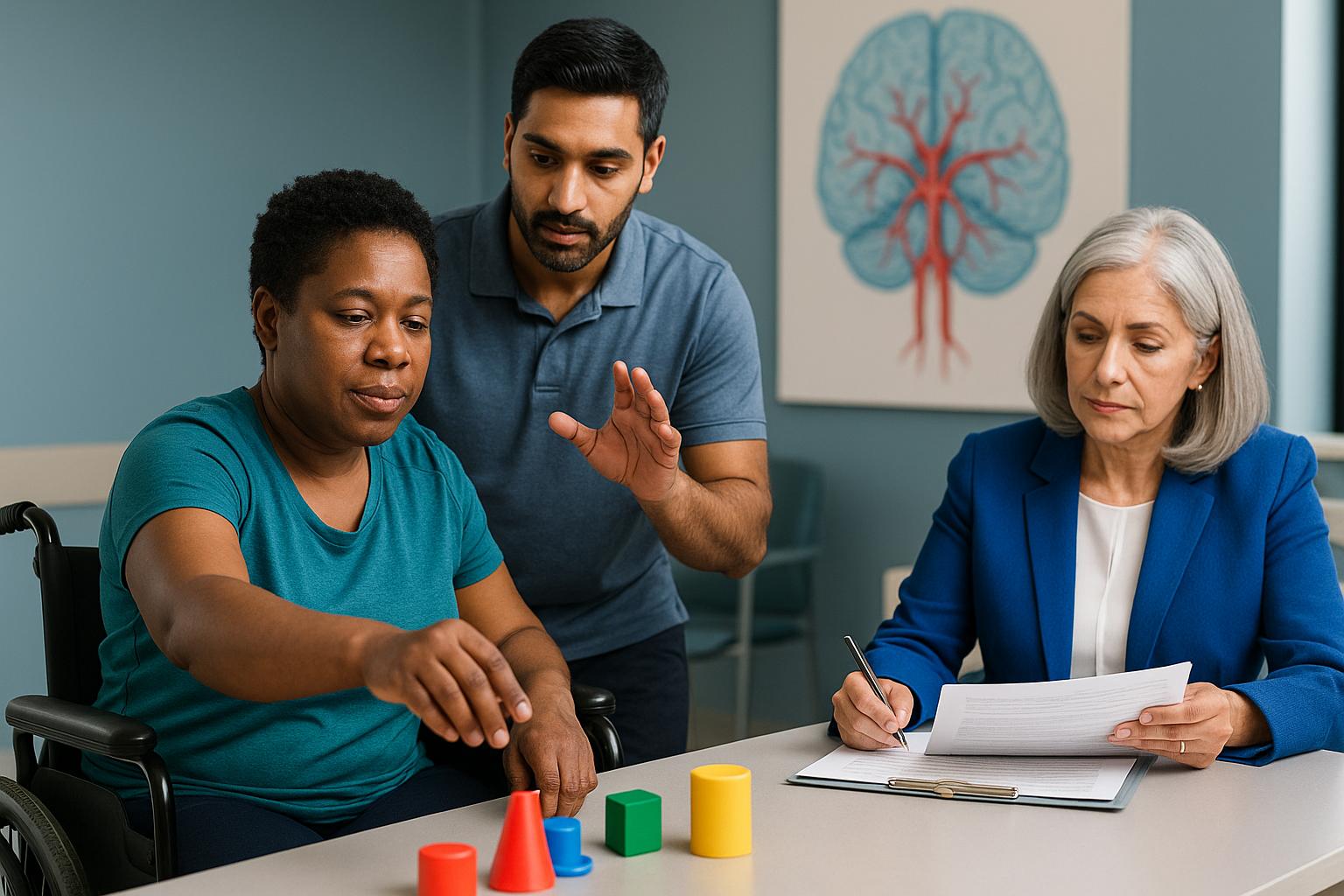

Cerebellar ischemia disrupts the coordination circuits that maintain balance and smooth movement. The spectrum of cerebellar infarcts within AICA territory varies based on which branches are affected and how far the ischemia extends. Balance deficits often persist because the cerebellum cannot regenerate lost tissue. Recovery occurs through neuroplasticity—where undamaged regions compensate for lost function—rather than tissue restoration.

The cerebellum compares intended movements with actual movements, making rapid corrections to maintain coordination. When cerebellar tissue dies from ischemia, this error-correction system fails, explaining why patients show normal strength but cannot coordinate movements properly. They may veer to one side, overshoot when reaching for objects, or struggle with tasks requiring precise timing. These deficits often improve partially but rarely resolve completely.

In my evaluations, I assess how cerebellar damage affects daily function beyond simple mobility. Patients may manage short distances with assistance but cannot navigate uneven surfaces or crowded spaces safely. This functional limitation matters more than imaging findings alone when determining long-term impairment.

Recovery Expectations After AICA Stroke

Recovery from AICA stroke depends on infarct size, location, and individual patient factors. Cerebellar stroke outcomes show significant morbidity, with functional trajectories varying widely between patients. Early rehabilitation focuses on compensatory strategies since cerebellar tissue cannot regenerate.

Most improvement occurs in the first three to six months after stroke. Patients regain some coordination through neuroplasticity, where undamaged brain regions assume new functions. Balance training and vestibular rehabilitation help patients adapt to persistent deficits. Complete recovery is uncommon when imaging shows substantial cerebellar involvement.

Hearing loss from labyrinthine artery occlusion typically remains permanent. Cochlear implants may restore some function, but natural hearing rarely returns. Facial weakness often improves partially, though complete resolution is unpredictable. Vertigo may decrease as the brain compensates for vestibular damage.

Long-term disability depends on whether patients can perform essential daily activities safely. Some patients return to work with accommodations, while others require ongoing assistance. Prognosis varies based on lesion location, with brainstem extension generally predicting worse outcomes than isolated cerebellar involvement.

My Approach to Stroke Rehabilitation and Impairment Assessment

Extensive experience in evaluating individuals with spinal cord and brain injuries suggests that stroke cases require careful attention to both imaging findings and functional outcomes. My practice emphasizes objective medical-legal consulting services for accurate assessment of impairment and recovery potential.

From my unique perspective with both medical and legal training, I assess how cerebellar damage affects daily activities beyond what scans alone reveal. Lesion location influences symptom severity; critical areas may lead to severe symptoms, while less critical regions may result in milder impairment. This relationship between anatomy and function matters when determining long-term limitations.

When reviewing AICA stroke cases, I focus on whether patients can perform essential tasks safely—not just whether they show improvement on standardized tests. Balance deficits may improve partially through compensation, but complete recovery remains uncommon when imaging shows substantial cerebellar involvement.

My dual training allows me to translate complex neuroimaging findings into clear documentation that both physicians and legal professionals can understand when assessing damages.

Conclusion

In summary, an AICA stroke occurs when blood flow stops in the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, causing sudden vertigo, hearing loss, facial weakness, and balance problems. Anatomic variability in AICA territory creates diagnostic challenges that affect both acute management and long-term recovery planning. MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging confirms the diagnosis by revealing characteristic lesion patterns in the cerebellum and brainstem. Recovery trajectories vary significantly, with most improvement occurring in the first six months through neuroplasticity and compensatory strategies.

As a physician and attorney with triple board certification in Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Spinal Cord Injury Medicine, and Brain Injury Medicine, I evaluate how cerebellar ischemia affects daily function beyond what imaging alone reveals. My dual training allows me to translate complex neuroimaging findings into clear documentation that explains how stroke location influences long-term impairment and disability claims.

Through Ciammaichella Consulting Services, PLLC, I provide specialized medical-legal services across licensed states such as Texas, California, and Colorado. I am available to travel for expert testimony and in-person evaluations when appropriate. This flexibility allows individuals and legal teams with complex cases to access consistent, expert analysis regardless of location.

If you would like to request a consultation regarding an AICA stroke case or need guidance on navigating disability and recovery, please reach out through my contact page.

This article is for educational purposes only and should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment options. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read in this article.

Frequently Asked Questions

What causes an AICA stroke?

An AICA stroke occurs when the anterior inferior cerebellar artery becomes blocked, usually by a blood clot or atherosclerotic plaque. The blockage stops oxygen delivery to the lower cerebellum and portions of the brainstem. Risk factors include hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and cardiovascular disease. Some cases result from arterial dissection or embolism from the heart. The exact cause influences treatment decisions and long-term stroke prevention strategies.

How long does recovery from AICA stroke take?

Most recovery occurs within three to six months after stroke onset, though some improvement may continue for up to a year. The cerebellum cannot regenerate lost tissue, so recovery depends on neuroplasticity and compensatory strategies. Balance training and vestibular rehabilitation help patients adapt to persistent deficits. Complete recovery is uncommon when imaging shows substantial cerebellar involvement. Hearing loss from labyrinthine artery occlusion typically remains permanent.

Can I work after an AICA stroke?

Return to work depends on your specific job requirements and residual functional limitations. Patients with desk jobs may return sooner than those requiring physical labor or precise coordination. Balance deficits, vertigo, and hearing loss affect workplace safety and performance. Some patients need accommodations like modified duties or assistive devices. I assess whether individuals can perform essential job tasks safely when evaluating long-term disability claims.

About the Author

Dr. Ellia Ciammaichella, DO, JD, is a triple board-certified physician specializing in Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Spinal Cord Injury Medicine, and Brain Injury Medicine. With dual degrees in medicine and law, she offers a rare, multidisciplinary perspective that bridges clinical care and medico-legal expertise. Dr. Ciammaichella helps individuals recover from spinal cord injuries, traumatic brain injuries, and strokes—supporting not just physical rehabilitation but also the emotional and cognitive challenges of life after neurological trauma. As a respected independent medical examiner (IME) and expert witness, she is known for thorough, ethical evaluations and clear, courtroom-ready testimony. Through her writing, she advocates for patient-centered care, disability equity, and informed decision-making in both medical and legal settings.